Where few dare to tread, child grief expert Gwenn Silva’s book steps up for families

Circle around, grab your friend’s hand — and spin!

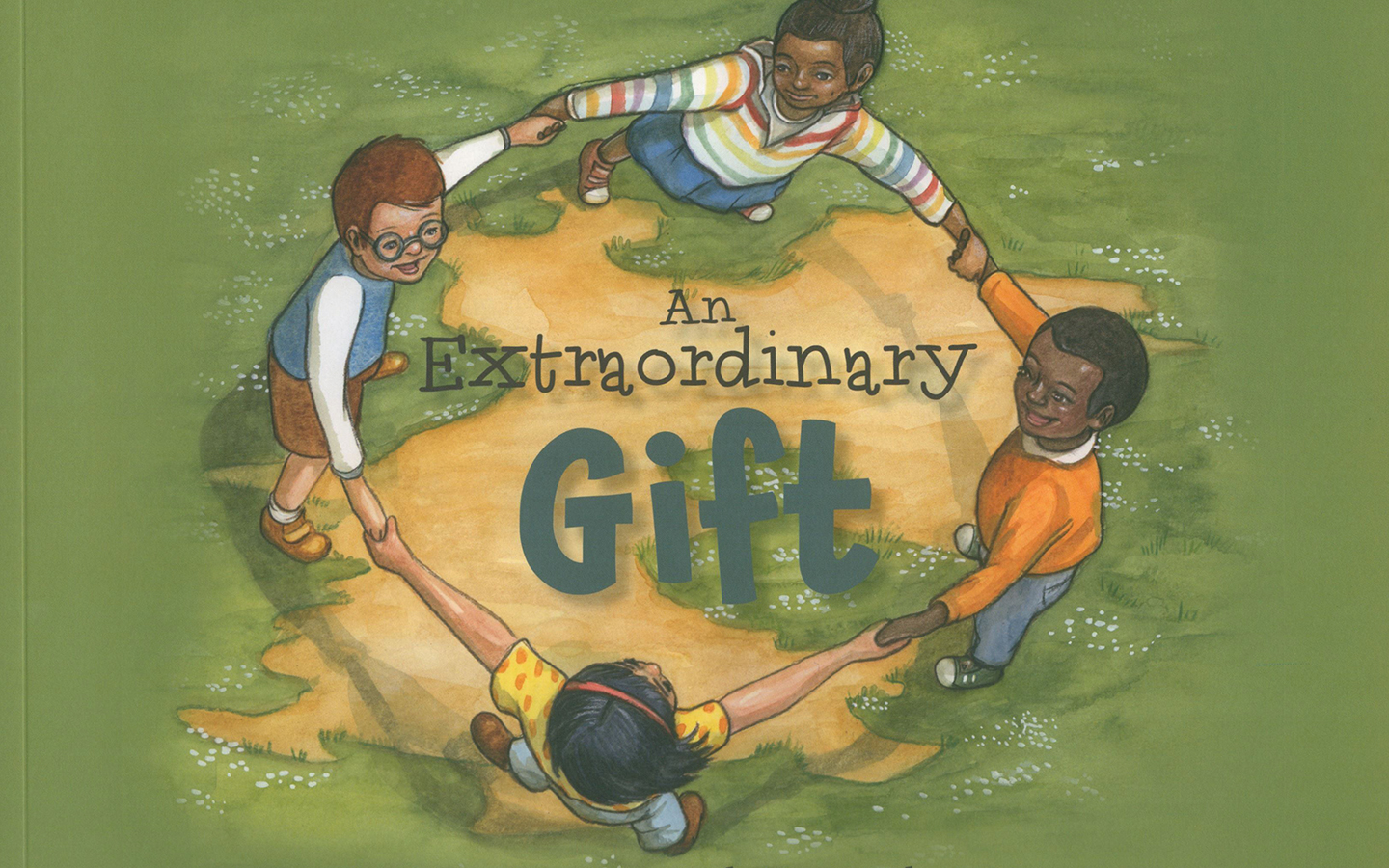

It’s easy to believe those were the instructions delivered to four grinning kids on the cover of counseling psychology lecturer Gwenn Silva’s first book, An Extraordinary Gift, released in April.

One child is dressed in a rainbow striped hoodie, another in yellow polka dot Tee-shirt. Hands clasped, arms outstretched, they make eye contact with one another as an unseen viewer looks down on what appears to be a contented ring of children at play. A closer look, however, at the subtitle running along the book’s bottom edge, Stories of Organ and Tissue Donation, signals to readers that the unexpected lies ahead.

A long-time instructor in HNU’s graduate counseling psychology program, Silva also serves as manager of Family Services for Donor Network West, a nonprofit that facilitates organ and tissue donation and procurement in Northern California and Nevada. Silva, a former child therapist, heads family grief support programs for the organization. Looking to provide resources, including age-appropriate books, for families, she went on the hunt several years ago for children’s books addressing the subject. Her search results yielded … nothing. No books on the subject then existed. More recently, she found one that told stories using animal characters. Not good enough, says Silva.

“We need to be more realistic with children,” says Silva, who was 11 years old when she lost her own mother to breast cancer. “We have to be willing to say some of the things that are hard.”

Nationwide, 125,000 people are on waiting lists for organ and tissue donation. One organ donor can save the lives of up to eight people and a tissue donor can heal more than 75 others, according to the Donor Network.

In June, Silva presented the publication at the Association of Organ Procurement Organizations Annual Meeting in the Washington, DC.

Among courses Silva teaches at HNU is “Trauma, Grief and Loss,” in which she says the issue of tissue and organ donation arises without her bringing it up. She’s already brought a copy to one class and expects it will assist students in better understanding children and grief.

Before writing a single sentence of the book, Silva first turned to the real experts: regular parents and kids who had not necessarily been affected by organ and tissue donation experiences. Silva sat down with groups of young people and grown-ups to find out what they knew — and didn’t — about the subject, particularly how parents talk to kids. “Parents are brilliant when it comes to knowing how to talk to their children and what language to use.”

The lessons helped her, along with a Donor West colleague, draft seven short fictional stories that formed the book’s content. Only the first chapter, “Tommy’s Parents,” is about a child’s death and organ donation. Others focus on the loss of a parent or grandparent. In one, a grandmother with fading vision receives a cornea transplant that allows her to see her newborn granddaughter.

Targeted to children ages 5 to 8, An Extraordinary Gift is meant to be read with an adult who can answer any questions. Activity pages follow each tale to help young children further externalize feelings they can’t articulate. Feedback from readers to date suggests that younger children as well as teenagers have been reading the book.

“The need was: We’d be in touch with parents who would say, ‘I don’t know how to talk with my child about the fact that his father died and his heart is now living in somebody else.”

Just this week, she says, she heard from parents of 8-year-old twins who had lost one child, decided to make a donation but didn’t know how to explain circumstances to the surviving twin. “We talk with (parents), but we now have something concrete we can give them as well.”

“I know what we did was the right thing,” Silva says. “Families are saying, ‘I wish I’d had this before.’”